It’s Pride Month 2024 and here I am in London – a city that has known how to party since the Middle Ages, and possibly before. A quick scan of some digital newspaper archives – and my own non-digital mountains of paper going back 300 years – reveals plenty of evidence of gay men in London having fun and getting into serious trouble. Let’s look at some of the dangers LGBT people faced just being themselves over the last two hundred years.

Cruising lands you in court

Gay men often met in well known places for a night-time assignation. In May 1747, The Penny London Post – a newspaper – reported that at 11pm one night, two men had been apprehended in Middle Moorfield, a district just north of the City of London, “attempting to commit sodomy”. One man managed to escape while the other was hauled off to Hicks Hall – a long demolished building that was the main courthouse in the part of London, based in Clerkenwell. The newspaper hoped the man would receive a severe punishment.

1761 saw another trial for sodomy at Hicks Hall with a local shopkeeper, Philip Marsh, found guilty of “assaulting” a butcher’s servant “to commit the detestable sin of sodomy”. He got a six month sentence and in addition was placed in the pillory at Clerkenwell Green on multiple occasions. The pillory being a wooden structure that held you in place by the head and hands while a mob pelted you with rotten fruit and vegetables. If a criminal was particularly detested, it wasn’t unknown for somebody to die from their injuries in the pillory.

Imprisonment and the pillory featured a great deal for same sex relations but there were cases where the death penalty was inflicted. That is not to say that the gallows of England were heaving with gay men. But homosexuals did end up being hanged. For example, in 1803 a man called Methuselah Spalding was sent to the gallows for gay sex.

DISCOVER: Perils of being LGBT in Bridgerton era London

The Gabriel Lawrence case – 1726

One very sad case that ended with the death penalty was that of Gabriel Lawrence in 1726 who regularly frequented Mother Clap’s Molly House. Just to explain the eighteenth century terminology – a molly house was essentially a gay bar with bedrooms attached. Not necessarily a brothel as such but a place where men could pay to have sex out of public view. Many of them would have been married so this was somewhere they could find a man, have some fun, and then return to their wives and an outward display of domesticity.

However, molly houses were targeted by the authorities. Undaunted by this threat of legal trouble, Margaret Clap ran the molly house that bore her name in the Farringdon district of London on Field Lane (now part of Saffron Hill). She had a regular and loyal clientele and seems to have been quite a character on the early eighteenth century London gay scene. But the end was nigh. Mother Clap’s Molly House was raided in February 1726 – more than likely after tip offs from customers paid to be informants. Sad to say that some gay men were prepared to commit such a betrayal for financial gain.

In this case, a certain Thomas Newton implicated Lawrence and he may have got other gay men arrested before in return for money . Newton convinced Lawrence to join him in a bedroom at Mother Clap’s and at that point, law officers stormed in and made the arrest. The court heard a description of the establishment:

“It bore the publick Character of a Place of Entertainment for Sodomites, and for the better Conveniency of her Customers, she had provided Beds in every Room in her House. She usually had 30 or 40 of such Persons there every Night, but more especially on a Sunday.”

And a touching description of how men conducted themselves at the molly house:

“In order to detect some that frequented it, I have been there several Times, and seen 20 or 30 of ’em together, making Love, as they call’d it, in a very indecent Manner. Then they used to go out by Pairs, into another Room, and at their return, they would tell what they had been doing together, which they call’d marrying.”

Gabriel knew he was in deep trouble and summoned character witnesses. He was a milkman and a friend who was a dairy farmer said the two had been drunk on many occasions and Gabriel had never attempted to seduce him. Other men testified that he was a sober character who had been married but his wife had died. He had a daughter aged thirteen.

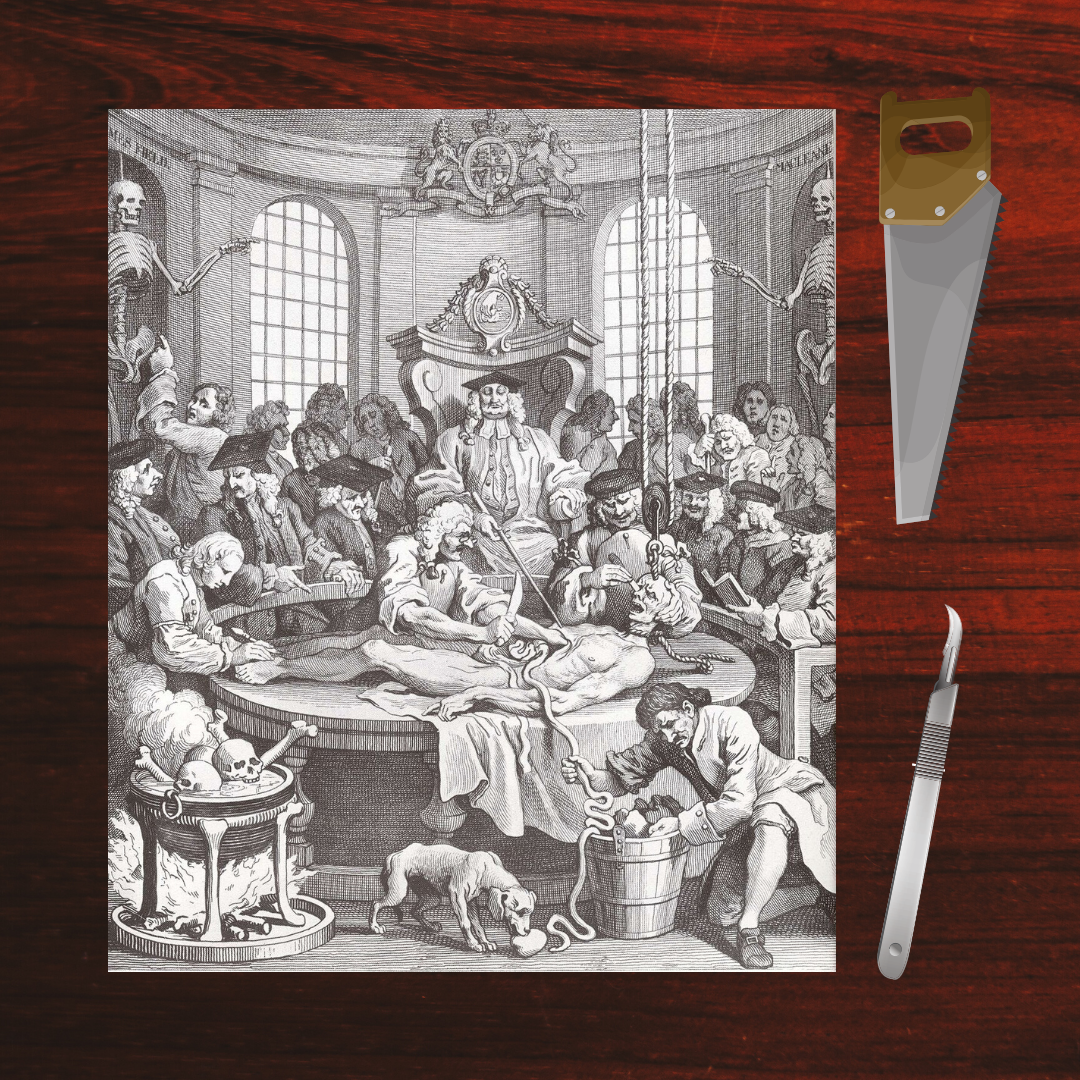

However, the judge was convinced that Gabriel was gay – which he more than likely was – and sentenced him to death. He was hanged at the Tyburn gallows (near today’s Marble Arch tube station) on May 9, 1726. His body was then taken to the Surgeons Hall to be publicly dissected – a common addition to capital punishment for working class people.

As for Margaret Clap – she disappears from the public record. It’s very likely she was both imprisoned and put in the pillory and may have died behind bars. Aside from the violence in the pillory, prisons were rife with typhoid and other incurable diseases.

DISCOVER: LGBT men hanged in London in 1743

Seduction or theft?

There are sometimes legal cases in the records of the London Central Criminal Court (the Old Bailey) that to modern eyes make little sense. Until you consider the predicament of the men involved. So, for example, on April 4, 1722, the Old Bailey heard the case of a John Casey – accused of violent theft against Francis Godelard.

Godelard had been sitting on a bench in St James’s Park near to Buckingham House in the evening. He claimed that Casey demanded money then wrestled him to the ground, breaking the waistband of his breeches as he struggled to find Godelard’s wallet. Horrified, he shrieked murder and “sodomite”. A soldier from the nearby barracks noticed something going on in the long grass and walked over expecting to find a man and woman having sex. Instead, he saw Casey holding the “Prosecutors privities”. Put another way, he was gripping on to Godelard’s testicles.

Godelard claimed a robbery was in progress and that Casey was a bad sort. But the court wasn’t convinced. St James’s Park was a notorious cruising ground and men caught in compromising behaviour often turned on each other to save their skins. Nobody wanted to dangle from the gallows for the London mob’s amusement. Casey was acquitted.

I should add that the Old Bailey archive is a fantastic resource for understanding the gay history of London. It does frame same sex behaviour as a criminal act – which regrettably it was at the time. But more importantly, it reveals a very visible and recognised world of same sex activity involving real people. This crushes the myth that homosexuality didn’t exist until psychologists coined the term in the late nineteenth century. It also sweeps away the confusing narratives from today’s post-modernists who baulk at acknowledging the existence of gay history.